|

Site History

During the hot, dry dig season, it is hard to imagine that the area we are excavating could have once supported a bustling community. Today, this portion of the Anatolian plateau seems parched, just barely suitable for farming. But thousands of years ago the confluence of two rivers, now mere streams, once provided ample water, and the surrounding arable land, ample food, for a population. Straddling a major East-West trade route, as well as a less traveled but distinct North-South route, the site was a perfect location for a town. People thrived at Çadır Höyük for at least six millennia.

Evidence of the first known settlement at Çadır Höyük, found at the bottom of a deep sounding on the south slope, has been radio-carbon dated to the Early Chalcolithic (5300-4500 BCE), though a Neolithic (ca. 5500 BCE) foundation may well lie underneath.

The proportionately smaller size of sites nearby suggest that Çadır may have evolved into a regional center by the Late Chalcolithic Period (3700-3200 BCE), frequented perhaps for a major local market or a bazaar for exotic trade goods.

In our trenches along the base of the southern slope, we have identified at least one Late Chalcolithic domestic structure, which was well-provisioned. We have also found a seemingly non-domestic complex having something to do with ceramics; perhaps a shop for renting cooking ware.

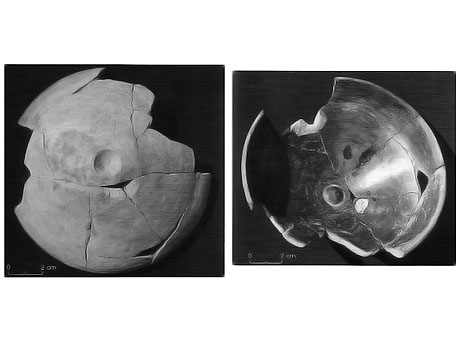

Dimpled Omphalos Bowls

Dimpled Omphalos Bowls

Click for more Prehistoric Artifacts

Within were once wooden shelves holding dozens of vessels of all shapes and sizes, including Omphalos bowls with dimples in the bottom, a staple Çadır pottery tradition. Outside these buildings were large, apparently private, courtyard areas. Public works in the excavated area include a stone platform and pathway, as well as a 1.5 meter thick enclosure wall split by a large stone gateway. Such public building projects give us a clue to the prehistoric power structure of Çadır Höyük, since an individual or group most likely would have needed authority over labor to accomplish them.

Floral and faunal remains in hearths show that the Late Chalcolithic diet consisted mainly of domesticated crops, augmented by a modest amount of beef, pork, goat, and the meat of several wild species. Çadır society also produced ceramics in the common central plateau style, but with some uniquenesses, such as the Omphalos dimples shown above.

Çadır Höyük at this time may have enjoyed a level of independence in its regional political environment. As yet, there has been no evidence of a power imbalance in interregional trade across the Late Chalcolithic Anatolian plateau. Its relationship with societies abroad may best be described as "mutual interaction" and "equal trade," possibly as part of broad eastern and western spheres. Contact or trade with Transcaucasia has been demonstrated by telltale sherds, a metal pin, and an andiron (a portable hearth) found at Çadır Höyük. Artifacts resembling contemporary Balkan styles found at Çadır and similar regional sites may indicate that the peoples of the central plateau also had some contact with Southeast Europe.

Near the end of the Late Chalcolithic-Early Bronze Transitional period (ca. 3100 BCE), the settlement appears to have undergone some type of disruption. The two complexes were destroyed by fire, the gateway was walled up, and subsequent construction and ceramics were of markedly poorer quality. Of note, the collapse of Mesopotamia's hegemonic Uruk period (4000-3100 BCE) occurred at about the same time as the difficult Late Chalcolithic-Early Bronze transition at Çadır Höyük. This may be simple circumstance, but excavations of Late Chalcolithic sites in Southeast Anatolia have demonstrated that there was regional interaction with Uruk. Although we know that the Uruk economic system did not penetrate into Cilicia or the Anatolian plateau beyond, the fact that the Çadır settlement did experience a drastic change at this time may mean that the Uruk collapse had some sort of ripple effect.

Çadır Höyük appears to have flourished during the Middle and Late Bronze Age (2000-1100 BCE). It was sometime during this period that the settlement outgrew its original boundaries, sprawling out into the surrounding fields. The site of the mound itself took on a new degree of importance in the town. The ruins of ancient complexes there have yielded a sizable collection of pottery and artifacts ranging from the Old Assyrian Colony (Karum) Period (2000-1700 BCE) to the time of the Hittite Empire (1400-1200 BCE). Of particular interest are a number of cultic artifacts, the earliest of which date from the Middle Hittite Period (ca. 1500 BCE), which may indicate the site's importance as a religious center.

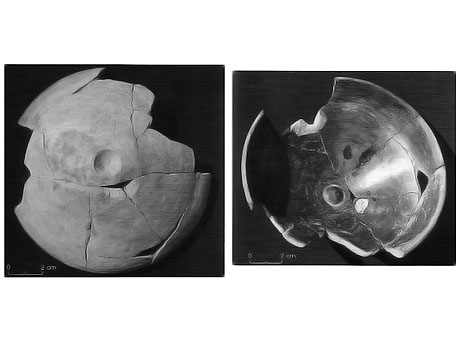

Hittite Libation Bowls

Hittite Libation Bowls

Click for more Bronze Age Artifacts

A monumental gate built in the time of the Hittite Empire supports that Çadır was a core city in the Hittite homeland. Mammoth rocks, many of which have since rolled down the hillside or been recycled in later construction, once formed a gateway five meters wide facing north, toward the Hittite capital, 70 kilometers away.

Çadır Höyük's apparent importance, the cultic artifacts found there, and the surrounding geography has led us to tentatively identify the site as Hittite Zippalanda. Epigraphic texts document the Hittite king's regular visits to this city and nearby Mt. Daha to perform sacred rites to the Stormgod of Zippalanda, describing the city and the surrounding area. We know from the impressive gateway that Çadır Höyük was a Hittite settlement of a significance on par with that of Zippalanda. Libation bowls and religious figurines show that religion was a factor in Çadır society. The texts corroborate Mt. Daha's height with that of a nearby hill, Çaltepe, as well as the distances involved in the king's journey. If Çadır Höyük was in fact Zippalanda, other regional ruins conveniently fit into our understanding of Hittite geography. A 40 meter by 80 meter stone enclosure near Çaltepe's summit may even be the temple at which the king performed the holy rites, although a cursory excavation of a portion of that area has not yet revealed any Hittite presence. More evidence will be necessary to make the claim definitive, but the body of evidence so far seems to support our conclusion.

To date, our excavations have revealed little about what happened at Çadır Höyük immediately after the Hittite Empire's collapse (ca. 1200 BCE). We have run across ceramics with Iron Age designs that otherwise relate more to second millennium construction, but must more thoroughly explore this level to find contemporary architecture.

Spindle Whorls

Spindle Whorls

Click for more Iron Age Artifacts

Our trenches have uncovered significant Middle and Late Iron Age (1000-300 BCE) architecture, which was built over or, in the case of the monumental gateway that stood well into the Late Iron Age, into the remains of the Hittite settlement. Among these ruins we commonly find sherds painted with Phrygian designs, including, nestled under a floor, one mostly intact pot that probably served as a house offering. We have also uncovered an industrial area, perhaps for processing leather or making textiles, which contained a large number of modified sherds worked into a variety of shapes. Some of these were probably spindle whorls (shown above), produced on site, along with some loom weights and a metal hook. There may even be Hittite precedent to a textile industry at Çadır Höyük, as some evidence associates Zippalanda and its cult with weaving. If the settlement was in fact Zippalanda, this may point toward a degree of continuity between Çadır's Iron Age society and its Hittite predecessor.

Hellenistic and Roman era ceramics have surfaced during excavations, but we have yet to uncover the actual settlements of these periods. Most distinct buildings were, in all likelihood, adapted or replaced by the prosperous Byzantine community (ca. 500 CE). Byzantine Çadır Höyük did not compare to the affluent cities of the coast, but, for an agricultural society in the central plateau, it did well. The city expanded even further; in a distant field, its outer walls can still be seen today. Care went into aligning stone foundations, keeping pavement even, and planning urban space. The presence of imported African red slip ware, or a high quality imitation, further attests to the site's prosperity at that time.

The mound, with its commanding view of the surrounding countryside, appears to have been strictly used as a citadel, featuring no construction along the slopes. The Middle Byzantine structures there have many of the qualities of a kastron, a defensive center of population with military and administrative functions. To what degree Çadır Höyük was occupied at this time – as an outpost, a garrison, or simply a local secure refuge – remains to be discovered.

Çadır Höyük's good fortunes waned with the eighth century Arab invasions, which probably disrupted life here. Buildings became more haphazardly constructed, and the quality of fine ware ceramics, now strictly of local manufacture, suffered. In subsequent years, the population probably lived under constant threat. By the eleventh century fine ware was unknown, and reconstruction was hastily executed. The invasions of the Seljuk Turks sealed Çadır's fate. Found on the citadel, a lead seal of Samuel Alusianos, the general who intended to battle the Turks at Manzikert, confirms that the settlement survived until at least 1071 CE.

Seal of Samuel Alusianos

Seal of Samuel Alusianos

Click for more Byzantine Artifacts

But shortly thereafter decline turned into collapse.

Although there is some minor evidence that a siege took place, it is also possible that the population simply fled. The skeletons of the Byzantine town's livestock were found locked away in a building at the summit, but there has been, as yet, no sign of human remains. Perhaps the townspeople intended to return, but were simply unable to do so with armed Seljuk bands roving unchecked across the Anatolian plateau. Scanty Seljuk Period (1100-1400 CE) finds suggest that the nomadic Turks of the Central Asian steppes had no interest in occupying the settlement. The town at Çadır Höyük lay abandoned. Years turned to decades, and the buildings fell into disrepair. Decades then turned to centuries, and the ruins were gradually sealed under a thin layer of dirt and vegetation. Which brings us to the mound in its present state today, a preserved capsule of some 6,000 years of history, just waiting to reveal its secrets.

|

Türkçe

Türkçe